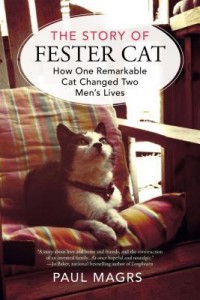

From when he first ambled into Paul Magrs’s yard—skinny, covered in flea bites, and missing all but one and a half teeth—Fester knew he’d found his family. Paul and his partner, Jeremy, thought it was the ragged black-and-white stray, tired from a rough life on the streets, who was in desperate need of support. But clever Fester knew better. He understood that it was his newfound owners who needed the help.

Over the course of seven years, the feisty feline turned the quaint Manchester house into a loving home. Through his fierce spirit, strong will, and calming energy, Fester taught Paul and Jeremy how to listen and breathe, how to appreciate the joys of simply sitting and singing (what Fester’s purrs sounded like to his silly humans), and how to find joy and contentment in life, even when dealing with hardship.

This is the true story of an extraordinary little cat whose gentle charm and trusting soul turned two young men into a family.

Now it’s time to sit at Paul’s desk.

His window is level with the top of his desk. The desk is a flat wooden table, with room for his laptop, a mugful of pens, and a small basket of notebooks. And there’s room enough for me to sit on. There are three basic desk positions for Fester Cat. First, there’s right in front of the laptop. I sit between Paul and his keyboard, pushing my face into his. I nudge him for attention. Somehow he snakes his arms around me and carries on typing, even as I’m kissing him. The warmth of the machine is wonderful.

Then there’s the more nonchalant positioning, on the right of the laptop. From here I can keep an eye on Paul, and lean over now and then to scratch my chin on the very corner of his computer screen. Sometimes I do this so well I leave some slobber on the glass, but he doesn’t mind.

Then—in some ways, best of all—I sit right in front of the window, with the whole of Chestnut Avenue spread before me. I have a magnificent view of the road in front of us and how it splits into two dead ends. Lots of traffic comes past here. Lots of kids in hoodies, school kids, mums with pushchairs, dodgy-looking blokes, and neighbours that I can recognise. Also, lots of cats. I watch them tracking about, hopping over walls, under gates, and brazenly down the middle of the road. Lots and lots of cats, not all of whom I recognise. And dogs and sometimes, late at night, foxes. I sit up, alert, riveted by the drama outside. To me it’s like the telly is to the boys, and I think they understand that.

Paul types away furiously for minutes and hours at a time. Then he stops abruptly. Then he does a bit more. Then he picks out a notebook and goes flipping through quickly, looking for something. Then he starts scribbling madly for page after page and then crossing things out. He uses pens that squeak against the page like baby mice. I can’t help myself hopping over and pushing my cold nose against his hand. If I really want his attention I go and sit on the pages of his notebook. If I think he’s been working too long and too hard and his attention is starting to fray, I go to interrupt him and I know it’s the right thing to do.

…

He talks to me at odd moments through the day. He takes it very seriously, knowing we’re having a proper conversation. Knowing I’m taking it all in. He tries out ideas on me.

“Spoiling you! Huh!” he says.

“Ungow,” I tell him. Surely it’s after twelve by now. Surely it’s almost time for lunch?

“You’re my first ever cat, Fester,” he tells me. “I’ve always wanted one. I always suspected that I might be a cat kind of person. But when I was a kid, Mam wouldn’t have one. She thought they were stinky, nasty things.”

“Ungow!”

“I know! And then, of course, as a student it was always about moving house each year and you couldn’t really have pets. Then it was about moving from city to city. And then me and Jeremy were living in different cities . . .

I like it when he tells me bits about their lives before I came along. I’m slowly building up a picture of who they both are. Paul uses far more words than Jeremy does, of course. He hardly ever shuts up. Only when he’s working or reading—and even then, it’s words, words, words passing through his mind.

“Really, I don’t even know the right way to carry on with a cat. I don’t know the right way to be.”

“Ungow.” I try telling him it’s fine. He doesn’t have to be any particular way. Just keep on doing his normal stuff. Cats don’t need entertaining or babysitting. If I wasn’t interested I’d be nowhere near you. I’d zip off somewhere and get on with something else. You’re okay. You sit quite still and you do some interesting stuff.

I especially like it when he goes off in one of his daydreams, between bouts of his tap-tapping at the keyboard. He stares into space out of the window just like a cat would. We sit there side by side, staring into the road, into other people’s windows, and into the sky.

Reprinted from The Story of Fester Cat by Paul Magrs by arrangement with Berkley, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, Copyright © 2014 by Paul Magrs.

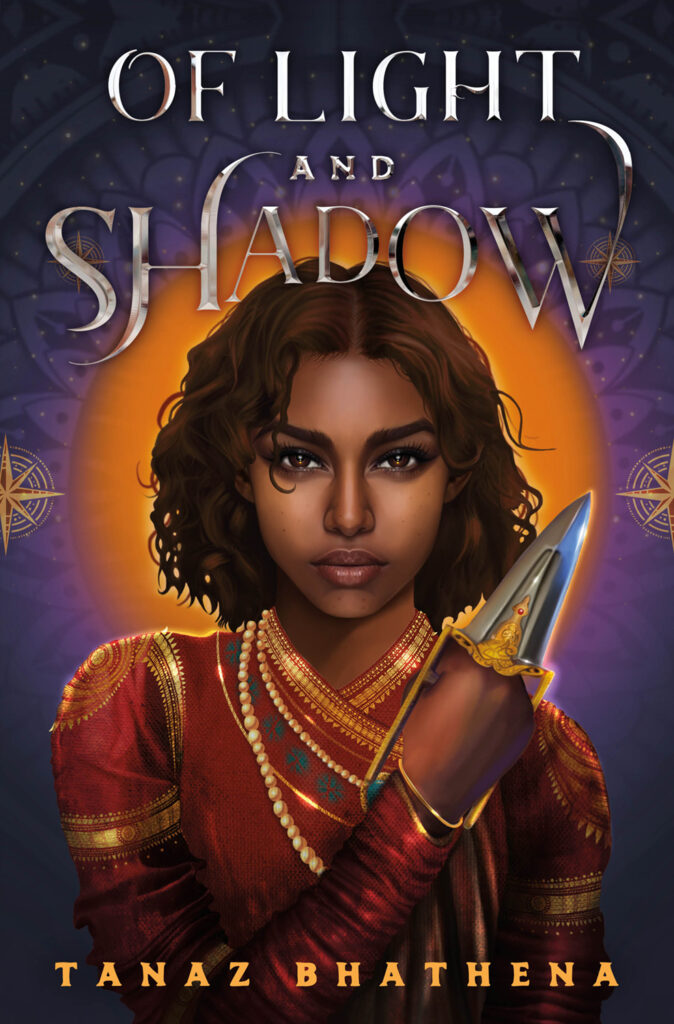

Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail

Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail![]()

Here We Go Again: My Life in Television

Here We Go Again: My Life in Television Scrappy Little Nobody

Scrappy Little Nobody Talking as Fast as I Can: From Gilmore Girls to Gilmore Girls, and Everything in Between

Talking as Fast as I Can: From Gilmore Girls to Gilmore Girls, and Everything in Between The Dead Inside

The Dead Inside The Tao of Martha: My Year of LIVING; Or, Why I’m Never Getting All That Glitter Off of the Dog

The Tao of Martha: My Year of LIVING; Or, Why I’m Never Getting All That Glitter Off of the Dog

I Don’t Have a Happy Place: Cheerful Stories of Despondency and Gloom

I Don’t Have a Happy Place: Cheerful Stories of Despondency and Gloom

This is a quick and easy read about Chelsea’s travels. She takes us through the various places she’s traveled, the friends who accompanied her and the insanity that ensued.

This is a quick and easy read about Chelsea’s travels. She takes us through the various places she’s traveled, the friends who accompanied her and the insanity that ensued. “Why are babies allowed to cry when they wake up, but adults crying when they wake is frowned upon? Babies are permitted to act like assholes whenever they feel like it and no one blinks, but if an adult throws a temper tantrum, all of a sudden it’s on YouTube.”

“Why are babies allowed to cry when they wake up, but adults crying when they wake is frowned upon? Babies are permitted to act like assholes whenever they feel like it and no one blinks, but if an adult throws a temper tantrum, all of a sudden it’s on YouTube.”